A trope is a rhetorical device that “establishes a predictable or stereotypical representation of a character[1].” A dog whistle is, perhaps, a particular type of trope intended for specific audiences who understand its meaning and significance. In a literary sense, “tropes become popular because they work. Tropes get used again and again because they speak to us on some deep level and connect with our experiences, fears, and hopes[2].”

Tropes may be grounded in a historical stereotype that becomes a shorthand for a group characteristic that demonstrates their inferiority or danger. Stereotypes that evolve into tropes, and in some cases, dog whistles, can be long-lasting and represent durable representations of entire groups.

They can be used and mobilized to categorize and create us/them distinctions. Indeed, given their presumably occult content, dog whistles specifically appeal to an in-group to build solidarity among members. Dog whistles draw on terms that speak at a deep level and connect to fears.

Anti-Semitic and anti-black tropes are so common that extensive lists have been compiled to alert people to their use. See, for example, the American Jewish Committee’s Glossary of antisemitic terms, phrases, conspiracies, cartoons, themes, and memes. And though the focus here is on rhetorical tropes, visual tropes are used in media that elicit specific expected responses or behaviors. See familiar racialized TV tropes here.

Typical contemporary anti-Semitic tropes include accusations of receiving “Soros’ money” (in my childhood, it was Rothchild’s money) or belonging to a cosmopolitan elite—a concept that Stalin utilized and was used recently by Putin concerning oligarchs. In Putin’s case, he is NOT saying they are Jews; he merely says they are dangerous like the “rootless cosmopolitans” of the Stalinist era.

There are tropes related to unhoused individuals, the most common and enduring being the use of “transient” to describe them. This indicates that unhoused individuals are not from “here”; they are not one of us; they are aliens.

And, of course, Lee Atwater’s entire Southern Strategy was a series of tropes that evolved as the N-word became unutterable in public. As Atwater made clear, that led to using other words that meant the same thing. Terms like busing, state’s rights (making a comeback in recent weeks), and later, economic issues related to welfare and the lazy poor.

Lately, a trope of seemingly recent origin has shown up nationally and locally in the news. This trope combines some elements of being soft on pedophiles, accepting child pornography, or, more insidiously, engaging in “grooming” children to be sexually abused by gay people.

I say seemingly recent origin because most of us relate these tropes to the rise of Q-Anon and the accusation that Democratic Party leaders and members are engaged in a global conspiracy to enslave and sexually abuse children.

While laughable in one sense, the Q-Anon conspiracy led to potentially serious consequences when a Q-Anon believer showed up armed at a pizza restaurant in Washington, DC. It is interesting how far into the mainstream this conspiracy has, since then, come in the form of a trope or several related tropes.

But this trope is not new. In an excellent Mother Jones article: Why Are Right-Wing Conspiracies so Obsessed With Pedophilia? Ali Breland traces the historical durability of not just the conspiracy but the tropes that have flowed from it. Indeed, this particular trope is one of the oldest anti-Semitic tropes—the trope of the blood libel. It has been around since the Middle Ages and accuses Jews of using children in human sacrifice.

The trope mobilizes our fear about protecting the most vulnerable members of our families and communities. It is bound up in our evolution and is always visceral—leaving a feeling of revulsion.

Perhaps, therefore, we should not have been surprised to see this trope rolled out during the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings of Ketanji Brown Jackson. Notice that no one had to say she had cozied up to pedophiles; they merely had to question her sentencing record. Once the trope was unleashed, it mattered little that the record shows that she has dealt with this category of crime in ways that are the norm. The doubt is sown; the trope has established Judge Jackson as a certain kind of character. In her case, this character is someone who will, if given a chance, endanger our children. She is a danger.

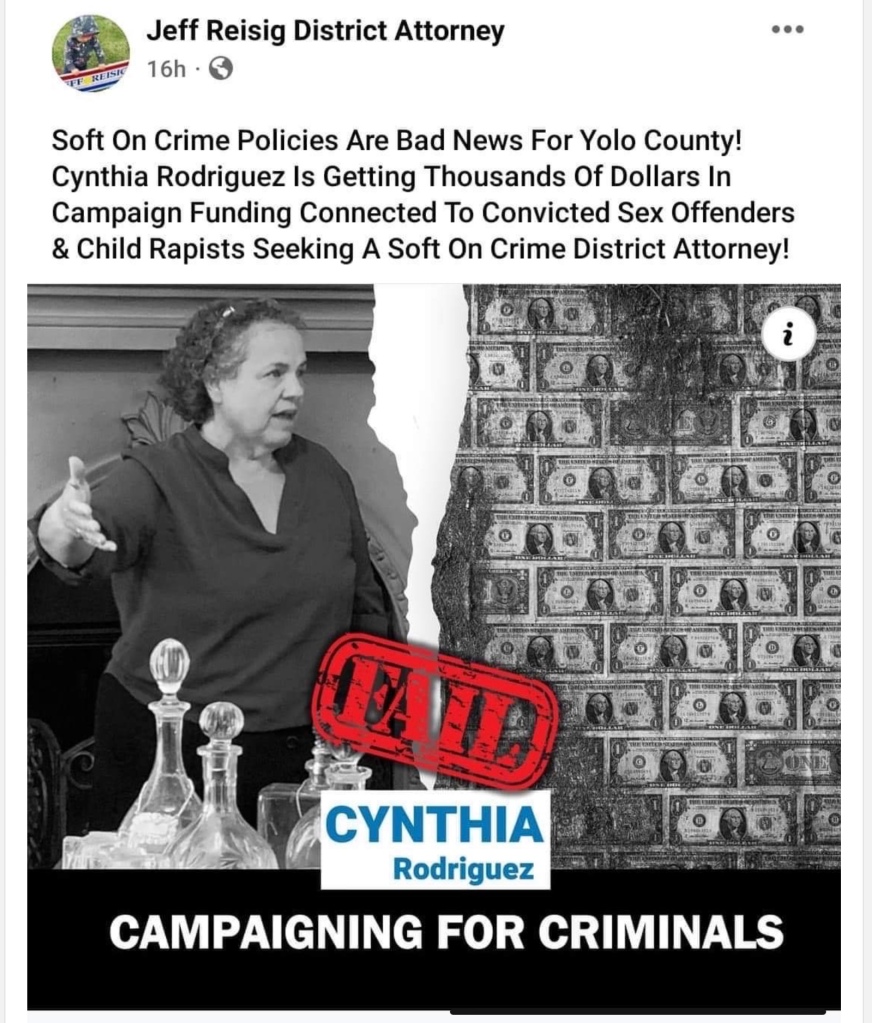

When District Attorney Jeff Reisig used a similar trope in a campaign advertisement (alert?) attacking Cynthia Rodriguez, he did the same thing. The trope is designed to place Ms. Rodriguez beyond the pale—not just someone who is likely to coddle criminals, but the worst kind of predators. She is a danger.

I will also note that the image in the Reisig ad also added a half-page of money images, which raises the question of whether statements about Soros’ support for so-called progressive DA candidates might be on the horizon. Reisig supporters in the last campaign used that trope.

(I must address the “accusation” briefly in the Reisig ad. The Rodriguez campaign received donations from two people associated with individuals convicted of sex crimes—sex with underage people. This is not under dispute. But the rapid move to unleash the “support for pedophiles” trope obscures the question of why those donations were made and, more importantly, whether they say anything about how Rodriguez will handle accusations of criminal behavior related to sex with children or child pornography that might come before her as DA. First, we know about these donations because the donors (or family members of the donors, more correctly) had committed and been convicted in very public ways. They are known offenders. Second, there is no legal reason they cannot contribute to a campaign, whatever their crimes. And third, perhaps their contributions say more about their treatment by the DA’s office than their support for the DA’s opponent.)

The ubiquity of media—social and informational—has multiplied appeals to stereotypes, led to the rapid proliferation of memes, and led to the recycling and repurposing of even ancient tropes. It is incumbent upon us, the consumers of these media, to recognize the way terms, concepts, and images are used to connect, especially in these times, to our fears.

We claim to want elections and governmental processes to be about “the issues,” but we too often allow tropes and other rhetorical mechanisms to fashion and dictate our engagement.

We do not need tropes in this race; we need substantive discussions and debate about such issues as AB 1928, the purpose of bail, appropriate and inappropriate uses of restorative justice, charging philosophies and plea bargaining, and mental health and criminality.